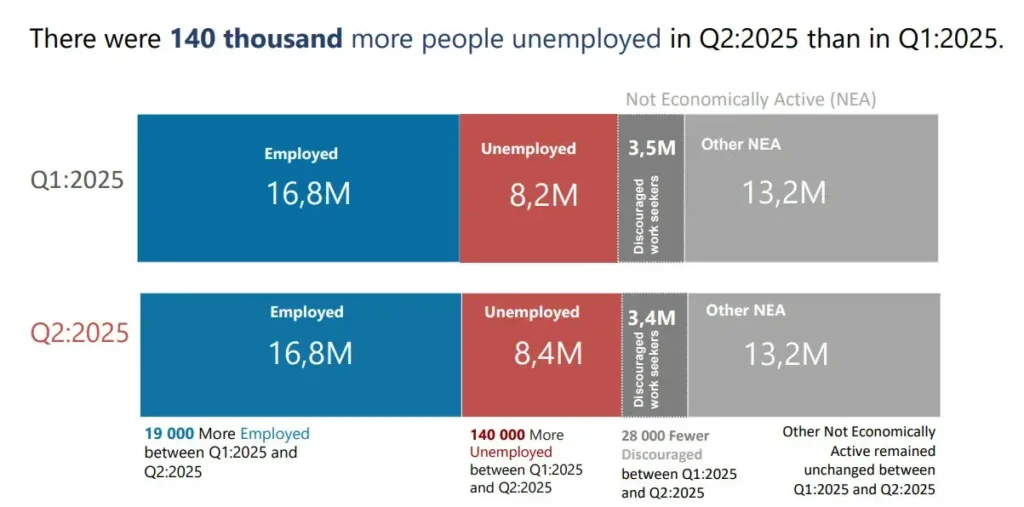

South Africa’s unemployment crisis has reached a breaking point. According to Stats SA’s latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey, the official unemployment rate climbed to 33.2% in Q2 2025, meaning more than 8.3 million people are actively looking for work but can not find it.

- South Africa’s Unemployment Crisis at a Glance (Q2 2025)

- The Numbers: What the Q2 2025 Data Really Shows

- Who’s Worst Hit

- Why This Is Happening — A Multi-Factor Analysis

- Skills and the Supply Problem

- Hiring Practices — How Employers Make the Problem Worse

- Employee Turnover & Retention — Hidden Costs and Solutions

- Sectoral Deep Dives

- Policy Levers and Public Accountability

- Recommendations — How to Fix the System

- Calling All Stakeholders to Action

Behind that headline number is a deeper problem: a shrinking pool of job opportunities, a workforce struggling with skills mismatches, and hiring practices that often exclude rather than include.

This is not just a crisis for the unemployed, it’s a warning for policymakers, business leaders, and educators that the way we create, fill, and keep jobs in South Africa needs to change.

South Africa’s Unemployment Crisis at a Glance (Q2 2025)

The Numbers: What the Q2 2025 Data Really Shows

The latest figures from Statistics South Africa’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) confirm that the country’s unemployment crisis is deepening. In Q2 2025, the official unemployment rate rose to 33.2%, up from 32.9% in Q1. That means 8.367 million South Africans who are actively seeking work are unable to find it.

But the official rate only tells part of the story.

When we look at the expanded definition of unemployment which includes discouraged jobseekers who have given up looking for work the rate jumps to 42.9%. This expanded figure exposes a hidden layer of economic inactivity that is often overlooked in political speeches and boardroom discussions.

Provincial disparities

Not all provinces are affected equally.

- Western Cape recorded the lowest official unemployment rate at 21.1%, highlighting the impact of regional economic strategies and sectoral diversity.

- Limpopo and Eastern Cape remain at the high end of the scale, with rates hovering well above 40%, driven by limited industrial activity and high rural unemployment.

Youth at the epicentre

The youth unemployment rate (ages 15–24) remains alarmingly high at over 60%, underscoring the severity of the skills mismatch in the job market. Many young jobseekers have the academic qualifications but lack the workplace experience employers demand, creating a catch-22 that fuels long-term unemployment.

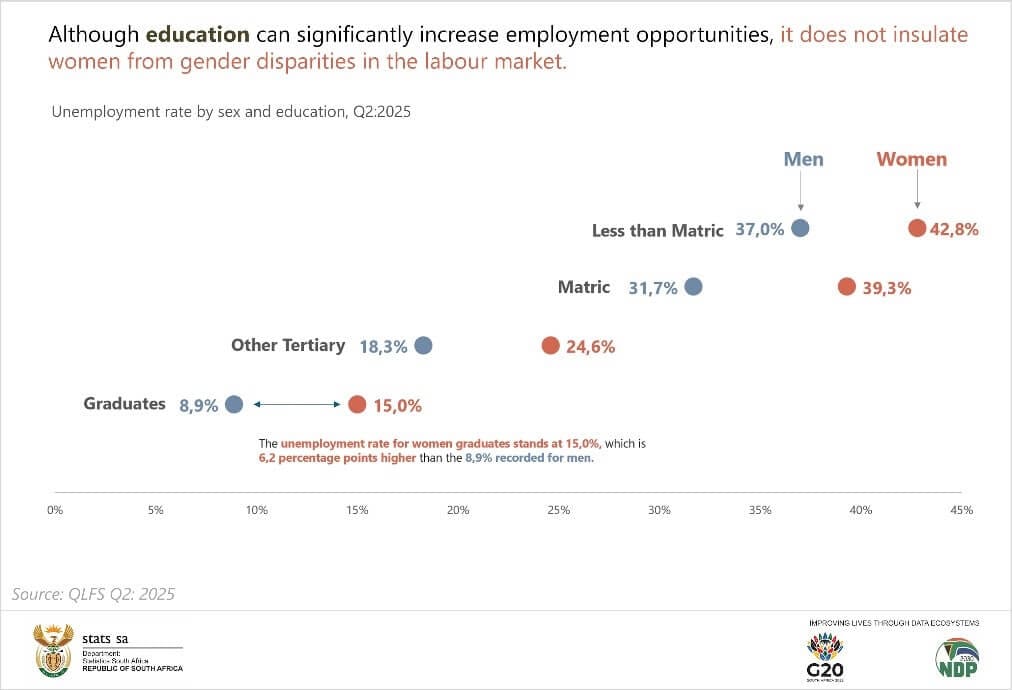

Education and employment

- Graduates enjoy the lowest unemployment rate at about 9%, but this still reflects a troubling trend for a group that should, in theory, be the most employable.

- Jobseekers without matric face unemployment rates above 45%, illustrating the enduring importance of basic education in employability.

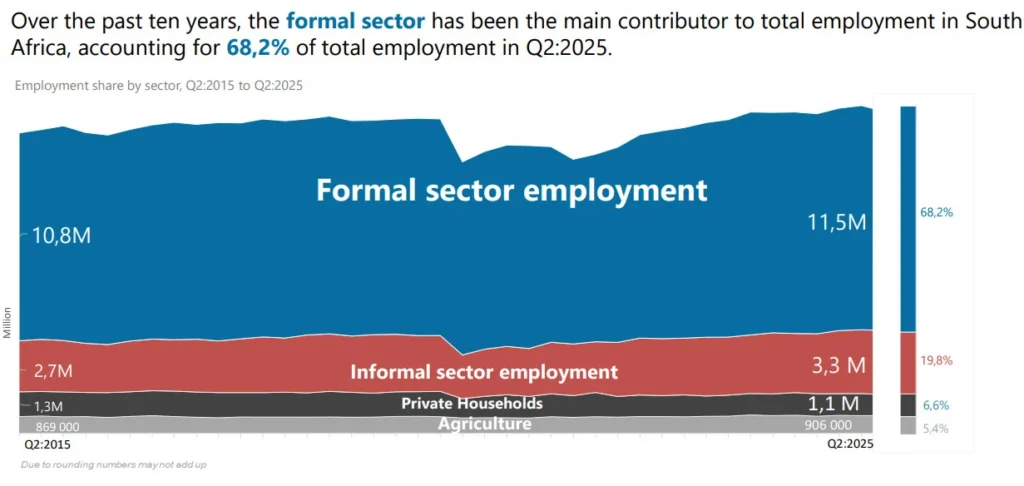

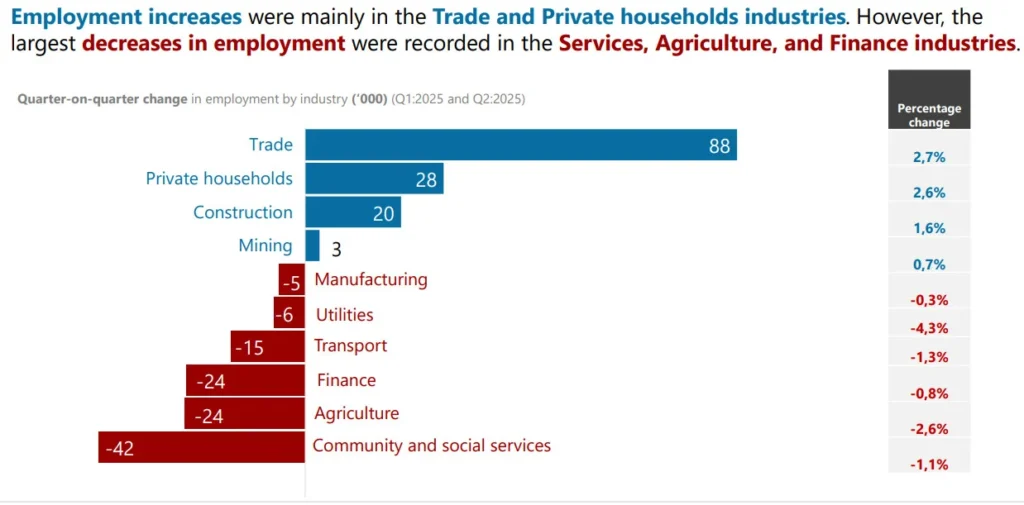

Sector performance

Some industries continue to shed jobs while others show modest growth:

- Manufacturing and construction saw notable declines in employment, reflecting weak investment and project delays.

- Community and social services, which include public sector jobs, added positions but not enough to offset losses elsewhere.

- Agriculture recorded seasonal gains, but these tend to be temporary.

These numbers make one thing clear: the unemployment crisis in South Africa is not just about a lack of jobs, it’s about the type of jobs being created, where they’re located, and who they are accessible to.

Who’s Worst Hit

South Africa’s unemployment crisis is not evenly spread. Beneath the national average of 33.2% lies a patchwork of disparities defined by age, education, gender, and geography. These fault lines reveal where the labour market is most fractured and where interventions are urgently needed.

1. The youth time bomb

- The unemployment rate for 15–24-year-olds is hovering at over 60%, making South Africa one of the worst performers globally in this category.

- For 25–34 year-olds, the rate is just under 40%, still staggeringly high.

- Many young people are NEETs; which means not in employment, education, or training; and risk becoming permanently excluded from the workforce.

- This group suffers most from the “experience trap”: entry-level jobs demand experience they cannot get without first being hired.

High youth unemployment is more than an economic issue; it fuels social instability, reduces tax revenue, and limits economic growth potential, to name a few.

2. The education divide

- Graduates have the lowest unemployment rate at around 9%, but this is up from pre-pandemic lows, showing that even higher education is no longer a guaranteed safeguard.

- Those without a matric face rates exceeding 45%, trapped by both a lack of qualifications and limited access to skills training.

- TVET college graduates often find themselves unemployed due to poor industry linkages and limited work placement programmes.

Without targeted skills alignment, South Africa will keep producing graduates both school and tertiary who the market cannot absorb.

3. Women bearing a heavier burden

- The unemployment rate for women is consistently 3–5 percentage points higher than for men.

- Women are more likely to work in informal, vulnerable jobs with little security or benefits.

- Care responsibilities, lack of affordable childcare, and workplace discrimination compound the challenge.

Closing the gender employment gap would not only boost household incomes but also improve national GDP growth potential.

4. Rural and provincial inequalities

- Western Cape enjoys the lowest unemployment rate at 21.1%, benefiting from a diversified economy and active investment in tourism, tech, and agriculture.

- Limpopo and Eastern Cape are among the hardest hit, with rates well above 40%, reflecting limited industrial development and infrastructure challenges.

- Rural jobseekers often face additional barriers: fewer local job opportunities, higher transport costs, and weaker access to networks that lead to employment.

Provincial disparities create unequal opportunities and contribute to internal migration, straining urban infrastructure and services.

5. The informal economy’s hidden struggles

While the informal sector absorbs millions who would otherwise be unemployed, it is unstable, underpaid, and unprotected. Many in this sector operate without formal contracts, access to credit, or social protections leaving them vulnerable to economic shocks.

Ignoring the informal sector means ignoring a major component of the real economy. With proper support, it could transition into a source of sustainable employment.

Bottom line: The unemployment crisis hits hardest among the young, less educated, women, rural populations, and those trapped in the informal economy. Targeting these fault lines with tailored skills development, inclusive hiring, and regional economic planning is critical if South Africa is to reverse its jobless trend.

Why This Is Happening — A Multi-Factor Analysis

South Africa’s unemployment crisis is not the result of a single factor; it is the outcome of multiple, interacting structural, economic, and policy challenges. Understanding these drivers is essential if policymakers, employers, and educators are to design interventions that actually work.

1. Economic stagnation and weak investment

- GDP growth has remained sluggish, averaging around 1–2% annually over the past three years.

- Low business confidence, political uncertainty, and infrastructural challenges and corruption have reduced investment and job creation.

- Key sectors like manufacturing and construction are contracting or growing at rates insufficient to absorb new entrants into the labour market.

The implication? Without stronger growth and investment, the private sector cannot create enough jobs to keep pace with the expanding workforce.

2. Structural skills mismatch

- Many unemployed South Africans lack the skills that modern employers require. Conversely, employers report difficulty filling mid- to high-skill roles, reflecting a skills supply–demand gap.

- Problems exist at multiple levels:

- Weak basic education leads to low numeracy and literacy, affecting employability.

- TVET colleges and universities often produce graduates with limited practical experience.

- Employers are not always engaged in shaping curricula, leaving graduates underprepared.

Producing more graduates without aligning training to real-world requirements perpetuates the crisis rather than alleviating it.

3. Hiring practices that exclude

- Over-reliance on 3–5 years’ experience for entry-level roles.

- Over-emphasis on degrees for roles that require aptitude rather than formal education.

- Biased screening for university prestige or geography.

- High use of short-term contracts that limit internal promotion and retention.

Even qualified candidates are filtered out before they can demonstrate their potential, worsening youth and graduate unemployment.

Learn more: Applicant Tracking System Resume Template to Beat the Bots

4. Labour market rigidity

- Strong labour protections are essential, but they can sometimes reduce flexibility for small and medium-sized enterprises to hire new employees.

- Minimum wage policies, while critical for workers’ rights, can unintentionally reduce entry-level opportunities if businesses cannot absorb costs.

A delicate balance between protection and flexibility is required to encourage both fair wages and job creation.

5. Technological change and automation

- Automation, digitisation, and AI adoption are reshaping sectors like manufacturing, retail, and financial services.

- Low- to mid-skill roles are at risk, while the demand for high-skill roles grows, widening the divide between available skills and available jobs.

Without upskilling and retraining programmes, workers displaced by technology will add to the ranks of the unemployed.

Learn more: 10 Careers That Could Disappear in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

6. Governance and policy implementation challenges

- Inefficient public sector recruitment, weak monitoring of SETAs, and fragmented skills development initiatives reduce the effectiveness of government programmes aimed at job creation.

- Corruption and mismanagement can divert funds from impactful interventions.

Even well-designed policies fail if implementation is weak or accountability is lacking.

Bottom line: The unemployment crisis is not just about “too few jobs.”

It is a complex system failure: slow growth, misaligned skills, flawed hiring, technological shifts, and policy gaps all reinforce one another. Any effective solution must be multi-layered, addressing both supply and demand, while holding all stakeholders accountable.

Watch: EPWP workers unpaid amid IDT tender scandal

Skills and the Supply Problem

A central driver of South Africa’s unemployment crisis is a persistent skills mismatch.

While millions of jobseekers remain unemployed, employers continue to report difficulty filling positions requiring both technical and soft skills. This disconnect illustrates that the problem is not only a lack of jobs but also a workforce unprepared to meet market demands.

1. Education and employability

- Basic schooling: Many learners exit the school system without adequate numeracy, literacy, or digital skills, limiting their ability to perform even entry-level jobs.

- TVET colleges: While Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges are designed to provide practical skills, graduates often struggle with workplace readiness due to limited hands-on experience and weak industry linkages.

- Universities: Graduates frequently have strong theoretical knowledge but insufficient exposure to real-world challenges, internships, or sector-specific skills.

Without aligning curricula with employer needs, graduates remain unemployed or underemployed, deepening the skills gap.

2. The most critical skill gaps

- Digital literacy and IT skills: Across sectors, basic digital competencies are increasingly mandatory.

- Critical thinking and problem-solving: Employers report a shortage of candidates who can adapt to complex, fast-changing work environments.

- Technical trades: Skilled artisans; electricians, plumbers, welders are in high demand, yet training pipelines are insufficient.

- Soft skills: Communication, teamwork, and professionalism remain weak in new entrants, affecting employability even for technically competent candidates.

3. Systemic barriers in skills development

- Limited employer engagement in curriculum design leads to training that does not match job requirements.

- Low uptake of apprenticeships and internships reduces practical experience opportunities.

- Fragmented recognition of credentials e.g., qualifications from different institutions or informal training makes it difficult for employers to assess skills accurately.

- Geographic and socioeconomic inequalities limit access to quality training for rural and disadvantaged communities.

4. Case studies of successful interventions

- Some private sector initiatives demonstrate how employer-led training can bridge the gap:

- Companies partnering with TVET colleges to co-design courses and provide paid internships.

- Graduate development programmes with structured mentorship and on-the-job training.

- Short learning programmes targeting digital and technical skills for unemployed youth.

These models show that well-structured interventions can reduce the skills mismatch and improve both employability and retention.

5. Visualising the skills pipeline

A clear representation of the education-to-employment journey helps identify bottlenecks:

School → TVET/University → Internship/Apprenticeship → Entry-level Employment → Retention/Promotion

- At each stage, there is leakage: dropouts, unprepared graduates, inadequate placement opportunities, or hiring filters that block entry.

- Targeted interventions at any of these points can significantly reduce unemployment if implemented strategically.

Bottom line: Closing South Africa’s skills gap is critical to resolving the unemployment crisis. It requires coordinated action from schools, TVETs, universities, SETAs, and employers to produce a workforce ready for the jobs that exist today and the jobs of the future.

Hiring Practices — How Employers Make the Problem Worse

While South Africa’s unemployment crisis is often framed as a supply-side problem, employer hiring practices play a significant role in perpetuating unemployment. Even qualified candidates frequently fail to secure work due to outdated, rigid, or biased recruitment processes.

Learn more: The Fair Pay Bill Could Change How You’re Hired—and Paid

1. Over-reliance on experience

- Many entry-level roles require 3–5 years of prior experience, creating a paradox for first-time jobseekers.

- Employers often overlook potential, aptitude, and transferable skills, instead prioritising a narrow checklist of prior work history.

Young and graduate jobseekers are systematically excluded, feeding high youth unemployment rates.

2. Over-emphasis on formal degrees

- Certain roles demand university degrees even when the tasks require practical skills rather than formal qualifications.

- TVET graduates and candidates with non-traditional credentials are often screened out, despite having the necessary abilities.

This contributes to the underutilisation of the existing skills pool, especially in technical trades and mid-level positions.

3. Biased or exclusionary screening

- Geographic preference: candidates outside urban centres may be rejected despite willingness to relocate.

- Prestige bias: candidates from certain universities or schools are favoured, limiting diversity.

- Gender and racial biases, whether conscious or unconscious, persist in some recruitment pipelines.

Talented candidates are filtered out before they even reach interviews, worsening inequality and unemployment.

4. Short-term contracts and precarious work

- Temporary contracts and gig-based roles dominate some sectors, offering limited training or advancement opportunities.

- Employers prioritise short-term cost savings over retention and internal development, leading to higher turnover and loss of institutional knowledge.

Even when jobs are filled, the workforce remains unstable, and career development is stunted.

5. Ignoring internal training and promotion pathways

- Companies often hire externally rather than upskilling existing staff for new roles.

- Limited mentorship, on-the-job training, and professional development programmes reduce employee retention and progression.

Talent remains underutilised, while unemployed candidates remain outside the system.

6. Actionable employer checklist

To reverse these trends, organisations can implement targeted reforms:

- Skills-based hiring: assess aptitude rather than relying solely on degrees or experience.

- Structured internships and apprenticeships: provide real work experience with clear pathways to permanent roles.

- Diversity audits: review recruitment pipelines to remove bias and expand candidate pools.

- Internal mobility: create clear promotion ladders and upskilling opportunities for existing employees.

- Retention metrics: monitor turnover and onboarding success to improve long-term workforce stability.

Bottom line: Employers have significant power to either exacerbate or alleviate the unemployment crisis. Reforming hiring practices, prioritising potential over pedigree, and investing in employee development are essential to unlocking South Africa’s workforce potential.

Employee Turnover & Retention — Hidden Costs and Solutions

While the unemployment crisis is often framed around job scarcity, another hidden factor is how existing employees are managed. High turnover and poor retention practices not only destabilise companies but also exacerbate unemployment by cycling workers in and out of temporary or low-quality roles.

1. The cost of turnover

- Replacing employees is expensive. Costs include recruitment, onboarding, training, and lost productivity.

- Studies show that turnover can cost 50–150% of an employee’s annual salary, depending on the role.

- Frequent churn prevents companies from building skilled, experienced teams, reducing competitiveness.

Businesses that fail to invest in retention inadvertently contribute to the unemployment crisis by not sustaining stable employment.

2. Causes of high turnover

- Toxic workplace culture: Poor management, lack of recognition, and limited career progression drive employees away.

- Mismatch of expectations: Many employees leave because roles do not align with advertised responsibilities or their skillset.

- Insufficient onboarding and training: Workers feel unprepared and unsupported, increasing early exit rates.

- Low wages and benefits: Pay and perks that don’t meet market or living standards push employees to seek alternatives.

3. Solutions for retention

Businesses can mitigate turnover while boosting employability:

- Progressive onboarding programs: Structured orientation and mentorship improve early engagement and performance.

- Career development pathways: Clear promotion ladders and internal mobility retain talent and reduce hiring costs.

- Continuous training: Upskilling employees not only fills skill gaps but increases loyalty.

- Competitive compensation and benefits: Align pay with market standards to reduce attrition.

- Employee feedback mechanisms: Regular surveys and engagement sessions identify and resolve workplace pain points.

4. The broader impact

- Companies that invest in retention contribute to a more stable labour market.

- Stable employment reduces unemployment pressure by keeping workers in meaningful roles longer.

- Employees gain skills and experience that increase future employability, supporting both personal and national economic growth.

Bottom line: Improving retention is not just a human resources concern, it is a strategic lever in addressing South Africa’s unemployment crisis. Employers who invest in their workforce reduce costs, improve productivity, and help close the gap between jobseekers and meaningful employment.

Sectoral Deep Dives

South Africa’s unemployment crisis does not affect all sectors equally. Understanding these variations is crucial for policymakers, employers, and educators who aim to design targeted interventions that create sustainable employment opportunities.

1. Manufacturing

- Employment in manufacturing has declined over recent quarters, due to weak investment, energy shortages, and global competition.

- Skills gaps exist in both technical trades (machinery, engineering) and middle-management roles.

- Opportunities: Upskilling programmes for machinists and technicians, coupled with incentives for investment in local manufacturing, can generate immediate employment.

2. Construction

- Growth in construction is highly project-dependent; unemployment fluctuates with infrastructure spending.

- Short-term contracts and seasonal hiring dominate, leaving many workers unemployed between projects.

- Opportunities: Government-backed infrastructure projects could include apprenticeship quotas to train young workers while creating sustainable jobs.

3. Agriculture

- Seasonal employment is common, particularly in rural provinces.

- There is a shortage of skilled farm managers, technicians, and agronomists.

- Opportunities: Training and mentorship programmes in modern agricultural practices, plus mechanisation and irrigation projects, could stabilise employment and increase productivity.

4. Services (Retail, Hospitality, Health, Social Services)

- Retail and hospitality employ large numbers of youth and women, but wages are often low, and jobs are insecure.

- Public sector employment in health and social services has grown slightly, but bureaucratic hiring delays prevent timely absorption of qualified candidates.

- Opportunities: Upskilling service-sector workers in digital tools, customer management, and specialised care services can improve employability and retention.

5. ICT and Technology

- Rapid digitalisation has created a demand for software developers, IT support, data analysts, and digital marketers.

- However, local supply of qualified candidates is limited, leaving vacancies unfilled.

- Opportunities: Private–public partnerships in tech education, coding bootcamps, and certification programmes can quickly generate job-ready talent.

6. Mining and Energy

- Employment in mining has been stable but capital-intensive, limiting new hires.

- Skills gaps exist in engineering, geology, and technical maintenance roles.

- Opportunities: Investment in green energy projects and mine rehabilitation programmes can create jobs while building long-term technical capacity.

Bottom line

- Sector-specific strategies are essential to addressing the unemployment crisis.

- Labour-intensive sectors such as construction, agriculture, and services can absorb more workers quickly if combined with targeted skills development.

- High-skill sectors like ICT, mining, and green energy require deliberate training pipelines to fill specialised roles.

- Coordinated action across sectors ensures interventions are both efficient and equitable, tackling unemployment where it is most severe.

Policy Levers and Public Accountability

South Africa’s unemployment crisis cannot be solved by employers or jobseekers alone. Effective government policy, rigorous oversight, and public accountability are essential to create an environment where jobs can be generated, skills are aligned with demand, and labour market inequalities are reduced.

1. Strengthening skills development frameworks

- SETAs (Sector Education and Training Authorities) must be fully functional and accountable, ensuring training funds reach programmes that match industry needs.

- Curriculum alignment: TVET colleges and universities need closer collaboration with employers to ensure graduates are work-ready.

- Apprenticeships and internships: Government incentives for companies to provide structured workplace learning can bridge the gap between education and employment.

2. Labour market reforms

- Entry-level hiring incentives: Tax breaks or wage subsidies for hiring youth and first-time jobseekers can reduce barriers to entry.

- Flexible yet fair labour policies: Balancing worker protections with the ability for SMEs to hire cost-effectively encourages sustainable employment growth.

- Promotion of internal mobility: Policies encouraging firms to upskill and promote internally can reduce unnecessary external hiring, stabilising employment.

3. Regional and provincial development

- Government investment should prioritise provinces with high unemployment, such as Limpopo and Eastern Cape.

- Public infrastructure projects must integrate job creation targets, particularly for youth, women, and rural populations.

- Support for local small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can stimulate regional employment while building economic resilience.

4. Transparent monitoring and accountability

- Public reporting on unemployment trends, skills development outcomes, and job creation programmes ensures policymakers and citizens can track progress.

- Audits and oversight mechanisms for SETAs, government-funded training, and public employment initiatives can prevent misuse of funds and ensure impact.

- Civil society, media, and industry bodies should hold government accountable for achieving measurable employment outcomes.

5. Collaboration between stakeholders

- Government, business, labour unions, and education institutions must co-create solutions.

- Sector-specific roundtables can identify gaps, forecast skill requirements, and align interventions with labour market realities.

- Public-private partnerships in infrastructure, technology, and green energy projects can generate high-quality, sustainable employment.

Tackling the unemployment crisis requires bold, coordinated, and transparent action. Policy levers exist, but without rigorous public accountability and multi-stakeholder collaboration, reforms will remain limited and unevenly implemented. Effective governance is the linchpin that can turn analysis into real, measurable impact.

Recommendations — How to Fix the System

Addressing South Africa’s 33.2% unemployment crisis requires coordinated action across multiple fronts: skills development, hiring practices, employee retention, sector-specific strategies, and policy reform.

Below are evidence-based recommendations for all stakeholders:

1. Skills Development

- Align education with industry needs: Schools, TVETs, and universities must collaborate with employers to ensure graduates are job-ready.

- Expand practical training: Increase apprenticeships, internships, and on-the-job learning opportunities.

- Digital and technical literacy: Scale programmes in ICT, engineering, green energy, and other high-demand sectors.

- Upskilling and reskilling: Enable workers displaced by automation and technology to transition into new roles.

2. Reform Hiring Practices

- Skills-based recruitment: Shift from degree- and experience-centric hiring to competency and potential-based evaluation.

- Inclusive pipelines: Remove bias based on geography, gender, or institution; widen candidate pools.

- Structured entry-level programs: Create mentorships, graduate programmes, and paid internships to facilitate first-time employment.

3. Employee Retention & Workforce Stability

- Career progression pathways: Implement clear promotion ladders and internal mobility policies.

- Invest in workplace culture: Improve employee engagement, recognition, and professional development.

- Competitive compensation: Ensure wages and benefits match market realities to reduce churn.

- Continuous training: Keep employees’ skills current, increasing loyalty and productivity.

4. Sector-Specific Interventions

- Construction & infrastructure: Integrate employment targets and apprenticeship quotas in public projects.

- Agriculture: Promote technical training, mechanisation, and mentorship in rural areas.

- ICT & technology: Partner with private sector to run coding bootcamps and certification programmes.

- Manufacturing: Incentivise investment in factories, upskilling, and local production.

5. Policy & Governance

- Strengthen SETA oversight: Ensure training funds are effective and aligned with labour market needs.

- Youth employment incentives: Offer wage subsidies and tax breaks for hiring young, first-time jobseekers.

- Provincial development focus: Target investment in regions with highest unemployment.

- Transparency and accountability: Regular reporting on jobs, skills outcomes, and programme effectiveness.

6. Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

- Establish industry–government–education partnerships to co-design interventions.

- Include civil society and media in monitoring and accountability, ensuring reforms translate into measurable impact.

- Encourage public-private partnerships for scalable, sustainable job creation.

The unemployment crisis is multi-dimensional, but it is not intractable. Coordinated action across skills development, hiring, retention, sectoral strategy, and accountable governance can reduce unemployment, stimulate growth, and unlock South Africa’s workforce potential.

Reform must be urgent, deliberate, and sustained because the cost of inaction is too high for the economy, society, and future generations.

Calling All Stakeholders to Action

South Africa’s 33.2% unemployment crisis is more than a statistic it is a social, economic, and moral challenge. Millions of citizens are locked out of the workforce, young people face a lifetime of missed opportunities, and the economy suffers from wasted potential and lost productivity.

Solving this crisis is not the responsibility of one group alone. It requires coordinated action across all sectors:

- Government must implement clear policies, ensure transparency, and hold institutions accountable.

- Employers need to reform hiring practices, invest in employee development, and stabilise workforces through retention strategies.

- Educational institutions and SETAs must align curricula with labour market needs and expand practical training.

- Civil society and media play a critical role in oversight, advocacy, and ensuring that progress is monitored.

The time to act is now. By addressing skills gaps, reforming hiring practices, stabilising employment, and enforcing accountability, South Africa can turn the unemployment crisis into an opportunity: to build a workforce that is skilled, inclusive, and ready for the demands of a 21st-century economy.

The cost of inaction is too high but with deliberate, coordinated, and sustained efforts, change is possible. Every stakeholder has a role to play, and the moment to act is today.